SANKARA: A Revolutionary Lives On

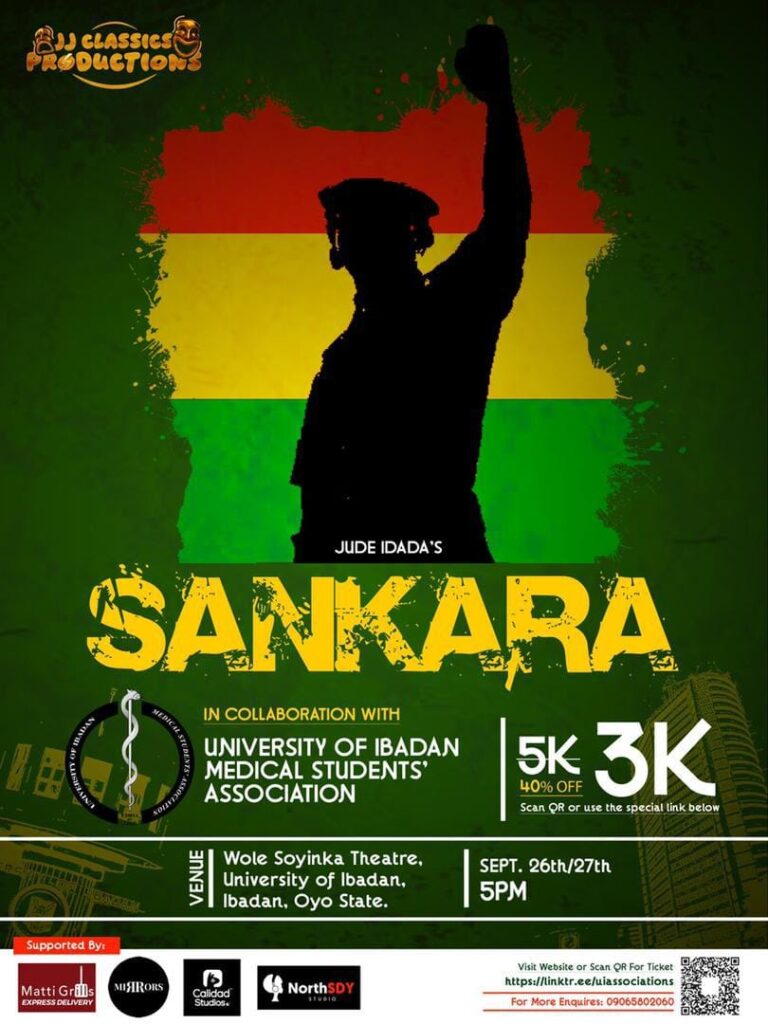

On the evening of Saturday, September 27th, the Wole Soyinka Theatre at the University of Ibadan was rife with activity. People gathered according to the play’s directives, in their best Ankara dresses, others more casually dressed, all united by the anticipation of seeing Sankara, written by Jude Idada and directed by Alai Toheeb. The crowd reflected a vibrant mix of students and lovers of theatre. I had only a faint knowledge of Thomas Sankara before that evening, a fleeting sense of his reputation as a great African revolutionary whose life was cut short. I had hoped the play would teach me not only about the man but also about the vision he lived and died for.

The production began promptly at 6:03 pm with the director, Alai Toheed’s simple request that the audience “pay attention and enjoy the play.” What followed next was nothing like we expected. Educative, compelling, to say the least.

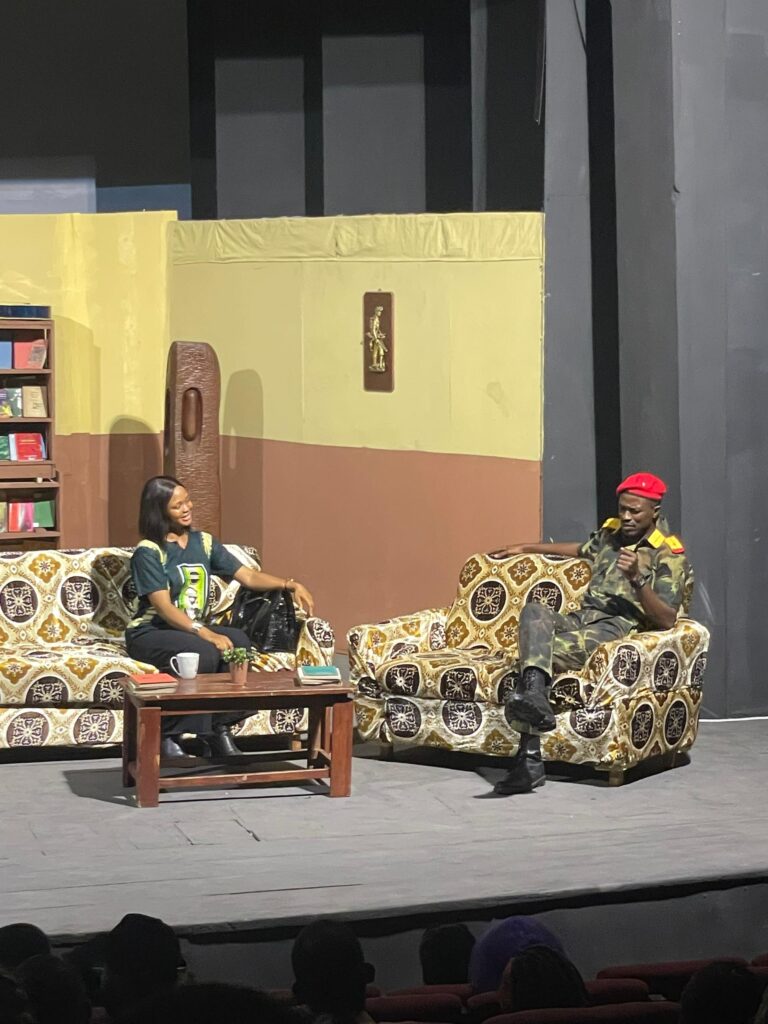

From the opening scene, Thomas Sankara was brought to life as more than a historical figure. Played as tall, dark-skinned, and charismatic, he was first shown playing the Burkina Faso National Anthem on his guitar, an anthem we eventually learn that he himself composed. This detail immediately set the tone for the play: Sankara as both soldier and artist, president and ordinary man. His humanity shone through in his interview with a female French journalist, where he insisted on being addressed as “Thomas” instead of “His Excellency.” The warmth and humility that drew his people to him were evident from the outset. His respect and love for women were evident right from the very first scene.

The play both educated the audience and weaved together Sankara’s passionate speeches, his anti-imperialist convictions, and his government’s remarkable achievements. His insistence on Burkinabé-made clothing, disdain for government excess, and reduction of official luxuries were recounted in vivid detail. He famously rode a bicycle to work and insisted his family do the same.

The list of his government’s achievements in just four years was breathtaking: banning female genital mutilation and child marriage, planting ten million trees to combat desertification, vaccinating millions of children, building schools, health centres, and water reservoirs, and ensuring food sufficiency. These accomplishments were not presented as dry facts; they were integrated into dialogue and interactions that allowed the audience to feel both the urgency and hope of his revolution but the play also showed Sankara’s flaws: his stubborn idealism, his refusal to anticipate betrayal, and his dangerous loyalty to those closest to him. His vision was soaring, but his inability to compromise or defend himself against treachery foreshadowed his downfall.

The dramatic tension of the play revolved around Sankara’s relationship with Blaise Compaoré, his friend and “brother.” Sankara’s trust in Blaise was unshakable, even as the audience saw the warning signs of betrayal. Blaise’s silence during discussions of women’s rights, of which Thomas had to explain, “he was a man of few words”, his ties to foreign powers, and his romantic involvement with an Ivorian woman who was a friend of the French all were carefully laid out by the playwright as evidence of his eventual treason. For the audience, the tragedy was not only political but deeply personal. We had watched Sankara defend Blaise, forgive him, and even refuse opportunities to have him arrested. His wife, Mariam Sankara, voiced the fears of a realist: she saw clearly that Blaise had turned long before Thomas did. Her attempts to protect her husband, and her plea that he prioritized his family over his ideals, added emotional weight to the unfolding drama, unfortunately, Thomas didn’t see her point.

The eventual conspiracy with imperialist backers and the climactic betrayal carried the emotional sting of inevitability. We saw it coming from the beginning and were caught with the feeling of helplessness as we could do nothing to stop it. We were not surprised when Blaise moved against him, but we still felt the disappointment, as though watching a friend betray another friend in front of our eyes. Watching him dance moments before his impending death, raised our cheeks as tears rolled down our eyes.

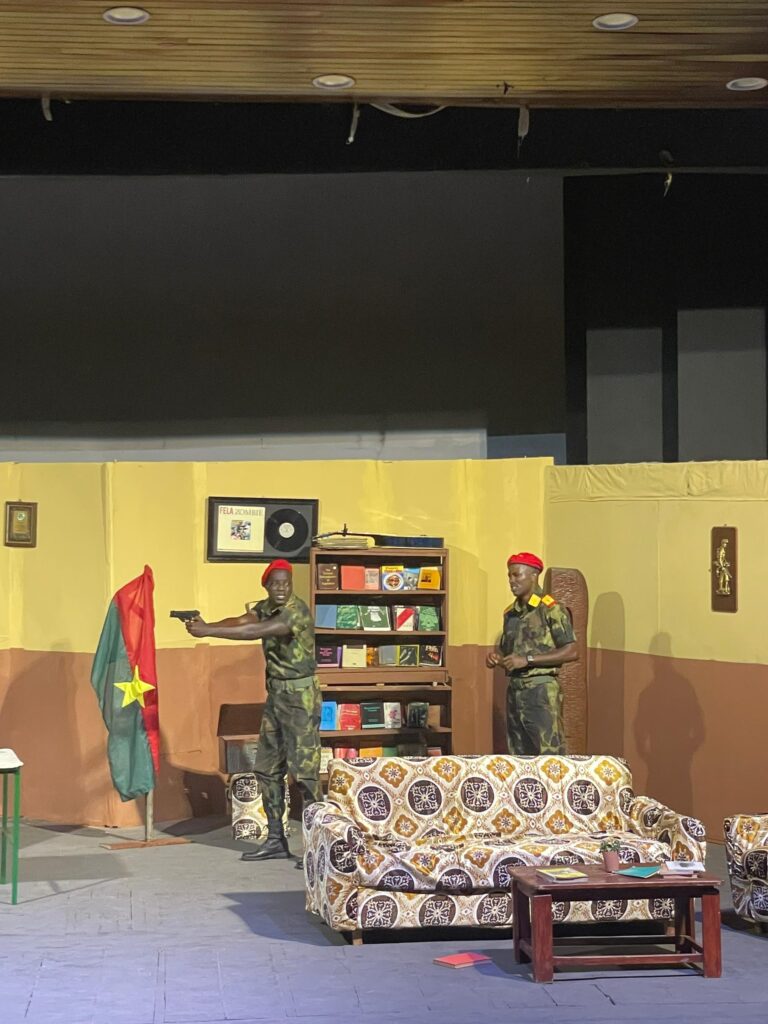

The success of Sankara lie not only in its script but in its execution. The staging was simple yet encapsulating, with a calming outlook which allowed the characters and dialogue to dominate the space. The actors were remarkable, their accents and delivery, Chef’s kiss! The actor playing Thomas Sankara embodied his charisma, combining fiery delivery in speeches with tenderness in his interactions with Mariam and his comrades. His body language was commanding yet approachable, a delicate balance that made him both believable and admirable. Mariam Sankara was portrayed with grace and strength, a voice of reason and pragmatism in the face of her husband’s idealism. Blaise Compaoré, by contrast, was played with a quiet, brooding presence, his silence as unsettling as his eventual outburst of betrayal. Their costumes stayed true to the story with the women in ankara throughout, and even small gestures like Sankara’s dancing or his casual manner with the journalist added depth to the characters. The simplicity of the set design ensured that the audience’s focus remained on the words and emotions, and in this, the production succeeded powerfully.

At its core, Sankara was not just a retelling of a revolutionary’s life but an exploration of timeless themes: the tension between idealism and realism, the fragility of trust, the cost of leadership, and the enduring power of ideas. Sankara’s insistence that he did not want to be the “face” of the revolution, because a revolution must outlive its leader, was presented as both noble and tragic. His refusal to spill blood, even to protect himself, made him admirable but also vulnerable. In his final moments, preparing himself mentally for martyrdom, he repeated the line that would linger long after the play ended: “You can kill a revolutionary, but you can’t kill his ideas.”

For a predominantly university-based audience, these words carried particular weight. At a time when many African nations still struggle with corruption, dependency, and lack of visionary leadership, Sankara’s story felt painfully relevant. His life and death stood as both inspiration and caution. The production moved through a wide emotional range: it made us laugh at Sankara’s wit, admire his simplicity, feel his love for his wife and children, and ultimately grieve his betrayal and death. When the gunfire that ended his life rang out, the theatre sat in silence. It was a silence heavy with reflection, sadness, and perhaps even guilt at how often Africa’s best leaders are dropped dead too soon. The play ended at 8:05 pm with the cast saluting the audience while Burkina Faso’s anthem played. It was a solemn yet uplifting conclusion, reminding us that though Sankara was gone, his ideals remained alive.

Sankara was more than a play; it was a history lesson, a moral reflection, and an artistic triumph. It balanced the grandeur of political vision with the intimacy of human relationships, allowing the audience to see not just the revolutionary but the man. I left the theatre both enlightened and unsettled. Sankara’s ideals challenged me to think about what it truly means to serve a people selflessly, and his tragedy reminded me of the dangers of blind trust in people. The performance was impeccable, the accents, costumes, and staging perfectly chosen to convey the message. The writer’s intent came across loud and clear: that Thomas Sankara’s story is not just Burkina Faso’s story, but Africa’s. Sankara is the kind of production that stays with you long after the lights go out. It teaches, it moves, and it provokes thought. I believe everyone should see this play at least once in their lifetime.

Wisdom Ladapo.