Revisiting Modesty: What Are Nigerian Universities Trying to Prove With Dress Codes?

There has always been something fascinating about how Nigerian universities, public and private, relate to what students wear. The lines between dress sense, morality, and disciplinary action have grown increasingly blurred, leaving many to ask: are Nigerian universities modelling education, or enforcing an outdated dress-policing system? Conversations surrounding student dress codes are no longer mere hallway debates — they are increasingly becoming matters of institutional policy, disciplinary action, and national controversy. Across both public and private institutions, students are facing growing restrictions on what they wear, how they style their hair, and how they present themselves on campus. With each new circular or disciplinary board decision, it becomes more evident that this isn’t just about clothing; it’s about control, power, and the definition of decency within a society that is still negotiating its postcolonial identity.

Historically, Nigerian higher education was modeled after British systems, which emphasized “respectability” as a standard for students. But what passed for respectability then was a projection of Euro-Christian values. Education, at its foundation, was designed not only to cultivate knowledge but also to reinforce a specific moral and cultural code deemed ‘appropriate’ by colonial standards. Neatness, modesty, and conformity were non-negotiable expectations. The legacy of this mindset lingers heavily in Nigerian academic institutions, where expectations about appearance continue to mirror antiquated ideas of discipline and morality. In 2025, those same values still control what our universities permit on campus. The difference? Today’s students are more aware, more expressive, and less willing to conform.

And yet, conformity persists. Despite Nigeria’s cultural richness and diversity, most universities operate a surprisingly rigid and homogeneous standard of dress. Private universities are often the most notorious, with cases of administrators shaving students’ hair, cutting braids in public, or barring students from writing exams due to dress code violations. In public universities too, while implementation may be less dramatic, the rules are no less harsh. One need not look far: at Obafemi Awolowo University, a recent decision extract dated June 13, 2025, categorically outlined numerous fashion choices that, if seen on students, would attract rustication. The list included “off-shoulder clothes,” “transparent wears,” “dreadlocks,” “micro/mini/skimpy dresses,” “hair braiding for males,” “multi-coloured braids,” and “heavy makeups.” The punishments? Rustication for one or even two semesters. For wearing rumpled clothes or a T-shirt with “obscene inscriptions,” a student may lose an entire semester. Such sanctions, it seems, are not only excessive but disturbingly out of step with the lived realities and freedoms of youth expression in a modern democratic society.

In a move that raised more eyebrows than it calmed, the same management of Obafemi Awolowo University, issued a public disclaimer disowning the above referenced dress code circular that had earlier gone viral, one bearing the university’s official logo, referencing Council approval, and listing severe penalties including rustication for minor dressing infractions like wearing dreadlocks or rumpled clothing. The university claimed the circulating document was not the officially approved version, despite its clear formatting and tone resembling typical administrative releases. It is deeply troubling that an institution of OAU’s calibre would allow such a document to be disseminated without internal checks. Whether it was approved or not, the fact that it emerged from within and gained enough legitimacy to be taken seriously is an indictment of the university’s internal coordination and communication channels.

Just when it felt like the abuse of dress codes couldn’t get more absurd, a recent incident at the University of Osun (UNIOSUN) went viral: students were arriving to enter exam halls only to have their slippers forcefully cut off by security agents. Some were stranded barefoot and disqualified from writing the exams, all because they wore slippers. Instead of addressing academic preparedness or exam logistics, the university prioritized policing footwear, choosing humiliation over support. This disturbing episode illustrates a deeper pathology: universities are fixated on punishing minor “infractions” of dress and grooming while ignoring pressing academic and mental health concerns. The cutting of slippers is not merely petty; it reveals how institutions deploy arbitrary rules to control and shame, even at the expense of students’ academic progression. The real scandal is not indecent dressing, it’s the absurd trivialities they elevate over student welfare. In viral videos from 2023 and 2024, staff members of some prominent private universities were seen cutting students’ hair and removing their braids in the name of discipline. Students, some of whom pay millions in tuition, are treated like inmates, their autonomy stripped in the name of religious or moral conformity. There is no appeals process, no room for dialogue, just forced compliance. Dress codes also frequently entrench classism. A student wearing second-hand clothes or one with a “rumpled” look might be shamed or accused of lacking “presentation.” But not everyone has access to polished wardrobes. Thus, what is deemed “indecent” often reflects poverty, not vulgarity.

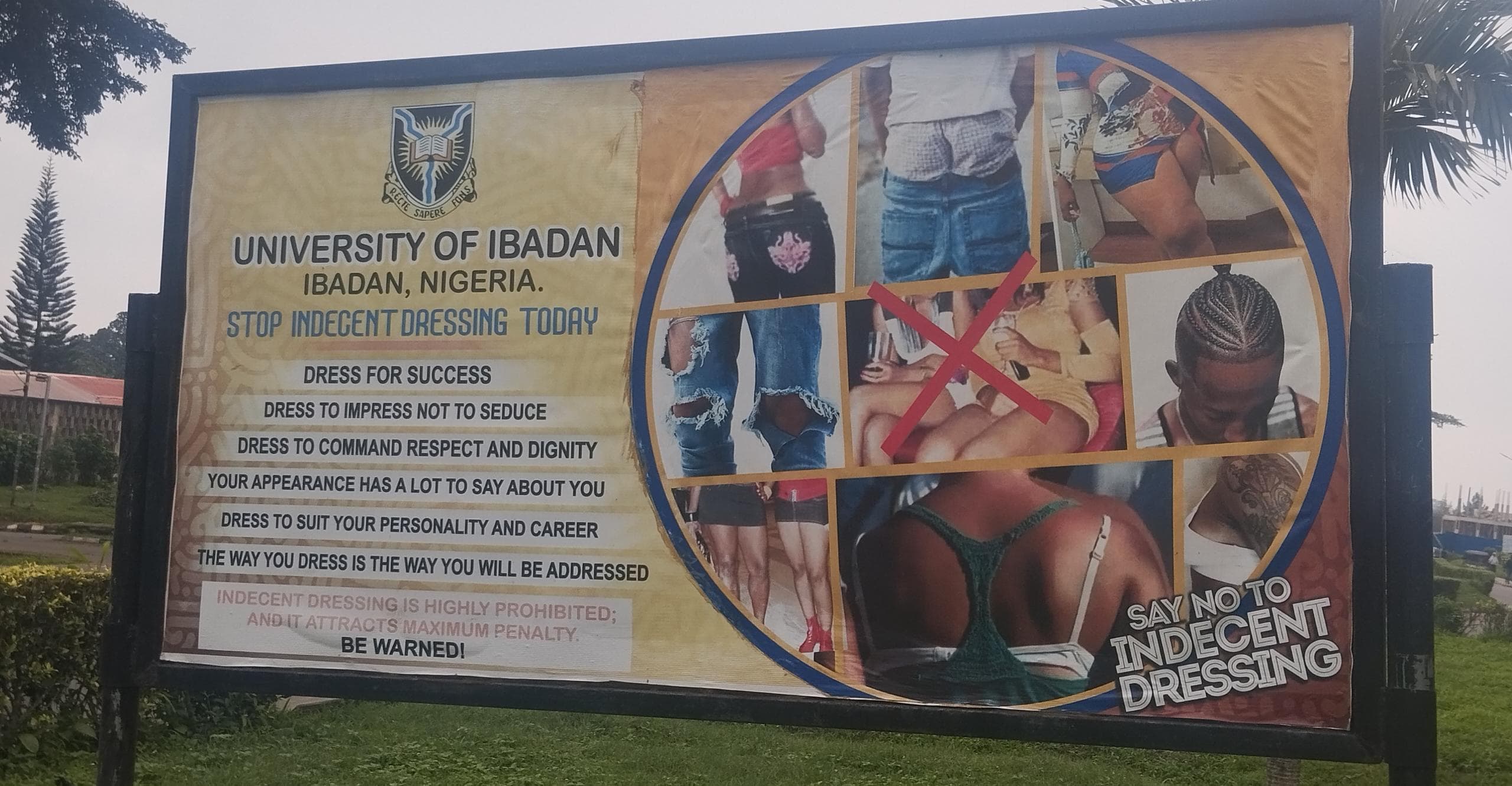

On the University of Ibadan campus, the situation is subtler but just as telling. Large billboards bearing vague standards of “decent dressing” remain visible across campus, yet enforcement is selective and unofficial. Interestingly, departments like Medicine, Pharmacy, Law, and Educational Management quietly enforce uniforms or professional attire under the pretense of preparing students for their future careers. While such rationale seems reasonable, it raises the question: where is the line between training and policing? The implications are far-reaching when students are more afraid of violating fashion rules than missing classes.

There are even contradictions within the system. Nigerian universities host concerts, fashion weeks, and pageants where celebrities and influencers show skin and wear avant-garde fashion. Yet, a student wearing ripped jeans can be chased out of class. The message? Glamour is fine on stage, but not in your daily reality, unless you’re a performer, not a thinker. The harm goes beyond clothing. Policing students’ appearances nurtures a culture of surveillance, shame, and anxiety. It teaches young people that their bodies are public property, always under scrutiny. For female students especially, this policing reinforces the idea that their value lies in how “modestly” they present themselves, not in their intellect or contributions.

Within student residences at the University of Ibadan, reports of informal dress codes abound. Regulations enforced by the hall warden of Queen Elizabeth Hall restrict female students from stepping out in outfits deemed unacceptable or wearing certain hairstyles. At the same time, male students of the University are frequently scrutinized for wearing dreadlocks, earrings, or tight jeans. The message is clear: to be a ‘proper student’ is to fit a narrowly defined, often outdated mould.

This brings us to the real question: what exactly is the purpose of these rules? To protect culture? To ensure order? Or to suppress autonomy?

University is supposed to be a space for learning and not just academic learning. It is where people come to figure themselves out, explore identity, and learn boundaries. But with strict dress policing, that growth is stifled. Worse still, it assumes that appearance determines character, an assumption that’s both simplistic and unfair. Are there limits to freedom of expression? Certainly. But the problem isn’t that dress codes exist; it’s the excessiveness and hypocrisy behind how they are enforced. If indecency deserves rustication, why does sexual harassment by staff often go without formal punishment? Why are some rules only enforced on the poor or less connected? Perhaps even more disturbing is the way discipline is meted out. There is little to no room for dialogue, reformative discipline, or restorative justice. Students are penalized with rustication, an academic death sentence for many over subjective infractions like “unwelcome hugging” or “unconventional face cap wearing.” It begs the question: what values are we truly upholding in Nigerian institutions of learning?

Dress codes in universities should reflect balance, not power. They should be grounded in community values, not the archaic fear of moral collapse. When universities suspend students for looking “too free,” they send one message: we don’t trust students to think for themselves. It’s not about encouraging nudity or dismissing cultural norms. It’s about balance, freedom, and empathy. Students should not be forced into cookie-cutter definitions of what is “acceptable.” Universities should strive to educate, not dictate.

This is not a call for anarchy or nudity in lecture halls. This is a call for clarity, fairness, and respect. If universities insist on dress codes, they must involve students in defining what those codes mean and engage students in conversations about grooming, professional contexts, and self-presentation without resorting to authoritarianism. Policies must be clear, consistent, and free from bias. Above all, punishments must be proportional, not life-altering. In a country with collapsing infrastructure, limited research funding, and mass youth unemployment, why are clothes our greatest concern? Shouldn’t Nigerian universities be more worried about brain drain, graduate unemployment, or the quality of instruction? Until we stop treating students like children or worse, criminals, Nigerian higher education will remain stunted, entangled in a moral panic that distracts from its real failures. Let our campuses be places of learning, not theatres of control.

The role of a university is to shape minds, nurture potential, and build citizens who can engage the world boldly and responsibly, not merely conformists who pass exams and follow dress codes. If our academic institutions must legislate clothing to such extremes, perhaps the deeper issue is not how students dress but how little we trust them to think for themselves.